Putin, the West, and the Inability to Understand What Russia Really Wants

Disclaimer: These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views, and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.

“The West today is looking at the problem in the wrong light: In seeking to stop Russia’s war, it focuses on Moscow’s artificial pretexts for its invasion of Ukraine and overlooks Putin’s obsession with the so-called Western threat as well as his readiness to use escalation to coerce the West into a dialogue on Russian terms. Ukraine is only a hostage.”[1]

In an earlier opinion piece for this forum, I pointed out that many of the negative consequences associated with major historical events on the international stage could have been mitigated, if not outright avoided, if policymakers, analysts, and decision-makers alike were better prepared to interpret global circumstances with more finesse despite existing constraints.[2]

The argument continued that, in many instances, both practitioners and observers of international relations suffer from analytical myopia. For instance, by obsessing over a single agent’s role in an international event, we ignore the complexity[3], which not only may contribute to the puzzling nature of the event but, to a greater extent than ever, characterizes the global system today.

In this piece, I continue this train of thought by delving deeper into the complex nature of the contemporary international system, using our inability to understand the Kremlin’s intentions on the world stage as a case in point. To help form my argument, I will employ the concept of complexity developed by Sargut and McGrath.[4]

Complex systems are characterized by three interlinked factors: the number of potentially interacting elements, how interconnected these elements are to one another, and the degree to which these elements differ from one another. As a result, the degree to which these three factors are present within a particular case determines just how complex a particular phenomenon may be considered.

Some leading experts in the management field ascribe our inability to discern the causality of events with a higher degree of accuracy to the complex nature of the circumstances surrounding us. As pointed out in an interview conducted by Tim Sullivan for the Harvard Business Review in 2011[5], the basic attribute of complexity is that it becomes harder for observers to define the direction and impact associated with cause and effect.

According to Sullivan, the main contributor to our inability to discern who did what to whom and why is the sheer multitude of actors present within a particular set of complex circumstances. For their part, each of these actors pursue selfish agendas by interacting with one another under various circumstances, including competition over market share for their products, military rivalry over disputed territory, or vying for limited social goods such as affordable housing or subsidized healthcare.

Expanding upon Sullivan’s article, Sargut and McGrath[6] state that while complex systems operate in well-established ways, it is the number and type of interactions among the various actors that put possible outcomes resulting from the interplay among actors and interests in a constant state of flux.

The level of unpredictability is not only attributable to the physical number of actors within a particular set of circumstances, but other factors also intervene. These include the degree to which actors are interconnected to and/or differ from one another in terms of their interests, as well as the extent to which interests evolve in relation to the overall circumstances that define the boundaries of a particular system at a particular point in time.

The authors continue to argue that the implications of unpredictability are tangible unintended consequences that take various forms[7]. It is these unintended outcomes that not only make the world around us more unpredictable but the job of interpreting complex events almost impossible either to the vantage point from which we observe events or our own cognitive limits in terms of grasping the effects our actions have the potential to impact others around us.

What you see depends on where you stand

Based on the discussion above, it now seems appropriate to draw the parallel between our general inability to perceive the whole picture tied to complex events while considering Russian international political and economic strategy within the contemporary context.

A strong argument is made by Varvara Vassilieva,[8] who attributes the dissonance between the West's perception of Russian intentions and the Kremlin's interpretation of international events primarily to the West's belief that Russia is a failed state. The country’s gradual turn away from Jeffersonian principles of governance espoused by Yeltsin towards a “jerry-rigged personalistic autocracy” established by Vladimir Putin has left the West with few frameworks to comprehend Russia’s strategic thinking outside that of the transition paradigm.[9]

However, that failure to evolve cannot simply be attributed to the personalities who held the Russian presidency. Instead, more substantive answers may be found in Russia’s own institutional development. The legacy that the Russian Federation has inherited is heavily influenced by the authoritarian structures of both the Czarist and Soviet systems whose principles are in direct conflict with liberal notions of individual freedoms and rights in the defense of international prestige, institutional stability, political legitimacy, and social order.[10]

For scholars such as Viacheslav Morozov,[11] some roots of both the West’s and Russia’s distrust of each other’s intentions exist within Russian society itself. On the one hand, the Kremlin understands that to remain a viable player in the international system, it needs to build upon the country’s existing human resources and turn intellectual capital into some form of global economic and political competitive advantage. However, contradictions seem to stand in the way of any wholesale modernization of Putin’s Russia.

Not only does Russia’s ruling elite fear the political, economic, and social instability of wholesale regime change, but for its part, society is not ready to give widespread support to a prolonged conflict with the West to maintain the domestic status quo either. Therefore, the Kremlin seeks to strike a balance between strengthening political control on the one hand while maintaining a semblance of economic modernization and social development on the other, so as not to disrupt the very institutional foundations upon which the current regime’s power and legitimacy rest.[12]

What is to be done?

The West currently faces a grave dilemma in terms of how to deal with the Kremlin over the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.[13] To begin with, the Kremlin feels that its long-standing strategic concerns are disregarded in the West’s thinking on Russia’s position in the international system. For the West’s part, any approach made towards Russia will continue to be hamstrung by our ideological devotion to the liberal democratic model of transition, which perceives Russia’s need for domestic security and stability as a threat to the values of the liberal international order.

To make better sense of this complex situation where tens of thousands of civilian lives are continually at stake and the stability of the world order in question, it is time for practitioners and analysts alike to cease obsessing about Putin as the source of Russia’s intransigence and instead broaden our perspective on Russia’s intentions from a more systemic perspective. Only then may we be prepared for a multitude of future possibilities as the conflict in Ukraine eventually plays itself out.

David Dusseault, PhD is an independent researcher and expert on Russian domestic political economy. As a graduate of Norwich University with a bachelor’s degree in international studies (1992), he received a Master of Arts in International Relations (2000) and a Doctorate in Political Science (2010) from the University of Helsinki in Finland. After completing his studies, David held various positions both in academia and the corporate sector, most notably as Acting Professor for Russian Energy Studies at Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki, Finland (2009 -2011), Senior Market Analyst for the Finnish natural gas distribution company Gasum OY, Espoo, Finland (2011-2015) and most recently, Professor of International Relations, School of Advanced Studies, University of Tyumen, Tyumen Oblast, Russian Federation (2018-2022).

[1] Stoyanova, T. (2022) What the West (Still) Gets Wrong about Putin. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/06/01/putin-war-ukraine-west-misconceptions/ (Accessed on 08.26.24)

[2] Dusseault, D. (2024) Sins of the Father. Voices on Peace and War the John and Mary Frances Peace and War Center at Norwich University. Available at: https://www.norwich.edu/topic/all-blog-posts/sins-father. (Accessed on 08.26.24)

[3] See McGrath, R. (2011) The World Is More Complex than It Used to Be. Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2011/08/the-world-really-is-more-compl. (Accessed on: 0827.24)

[4] Sargut, G., & McGrath, R. (2011) Learning to live with Complexity. Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2011/09/learning-to-live-with-complexity. (Accessed on 08.26.24)

[5] Mauboussin, M., & Sullivan, T. (2011) Embracing Complexity. Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2011/09/embracing-complexity (Accessed 24 July 2024)

[6] Sargut, G., & McGrath, R. (2011) Learning to live with Complexity. Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2011/09/learning-to-live-with-complexity

[7] Such unintended consequences manifest in various situations including when events interact without anyone meaning them to, or an event is an aggregate of individual elements, not a single occurrence, or when policies and procedures are no longer relevant to the situation for which they were initially created.

[8] Vassilieva, V. (2023) Legacies of Russian Authoritarianism: a political-cultural approach. Cambridge Journal of Political Affairs. Available at: https://www.cambridgepoliticalaffairs.co.uk/articles/onfzhlh1iuycvxn8hrjthdfm6j13m4. (Accessed on 08.26.24)

[9] Kotkin, S. (2024) The Five Futures of Russia and How America Can Prepare for Whatever Comes Next. Foreign Affairs. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/five-futures-russia-stephen-kotkin. (Accessed on 09.09.24)

[10] Vassilieva, V. (2023) Legacies of Russian Authoritarianism: a political-cultural approach. Cambridge Journal of Political Affairs. Available at: https://www.cambridgepoliticalaffairs.co.uk/articles/onfzhlh1iuycvxn8hrjthdfm6j13m4. (Accessed on 08.26.24)

[11] Morozov, V. (2018) Russia’s Internal Otherness. YaleGlobal Online. Available at: https://archive-yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/russias-internal-otherness. (Accessed on 08.26.24)

[12] Jacobson, Z. (2022). Putin’s Regime Spawns a New Generation of Kremlinologists. H-Diplo Essay 432- Commentary Series on Putin’s War. Available at: https://networks.h-net.org/node/28443/discussions/10141233/h-diplo-essay-432-commentary-series-putin’s-war-%C2%A0“putin’s-reign#_ftnref7. (Accessed on 08.26.24)

[13] Stoyanova, T. (2022) What the West (Still) Gets Wrong about Putin. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/06/01/putin-war-ukraine-west-misconceptions/ (Accessed on 08.26.24)

Read More

Sins of the Father

Disclaimer: These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views, and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.

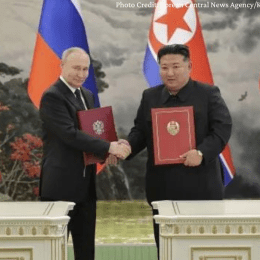

The U.S. Needs to Fully Realize the Strategic Significance of a New Russia-North Korea Pact

Disclaimer: These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views, and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.

The Al Hol, Roj Camps and Syrian Detention Complex: Cruel and Dangerous Foreign Policy

Disclaimer: These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views, and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.